Edmund Muskie

Edmund Muskie | |

|---|---|

Muskie as Governor of Maine, 1950s | |

| 58th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office May 8, 1980 – January 18, 1981 | |

| President | Jimmy Carter |

| Deputy | Warren Christopher |

| Preceded by | Cyrus Vance |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Haig |

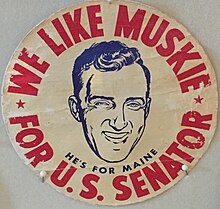

| United States Senator from Maine | |

| In office January 3, 1959 – May 7, 1980 | |

| Preceded by | Frederick Payne |

| Succeeded by | George Mitchell |

| Chair of the Senate Budget Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1975 – May 8, 1980 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Fritz Hollings |

| Chair of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1967 – January 3, 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Bennett Johnston |

| 64th Governor of Maine | |

| In office January 5, 1955 – January 2, 1959 | |

| Preceded by | Burton Cross |

| Succeeded by | Robert Haskell |

| Member of the Maine House of Representatives from the 110th district | |

| In office December 5, 1946 – November 2, 1951 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Cummings |

| Succeeded by | Ralph Farris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Edmund Sixtus Muskie March 28, 1914 Rumford, Maine, U.S. |

| Died | March 26, 1996 (aged 81) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5 |

| Education | Bates College (BA) Cornell University (LLB) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | U.S. Naval Reserve |

| Battles/wars | |

Edmund Sixtus Muskie[a] (March 28, 1914 – March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1980 to 1981, a United States Senator from Maine from 1959 to 1980, the 64th governor of Maine from 1955 to 1959, and a member of the Maine House of Representatives from 1946 to 1951. He was the Democratic Party's nominee for vice president in the 1968 presidential election.

Born in Rumford, Maine, he worked as a lawyer for two years before serving in the United States Naval Reserve from 1942 to 1945 during World War II. Upon his return, Muskie served in the Maine State Legislature from 1946 to 1951, and unsuccessfully ran for mayor of Waterville. Muskie was elected the 64th governor of Maine in 1954 under a reform platform as the first Democratic governor since Louis J. Brann left office in 1937, and only the fifth since 1857. Muskie pressed for economic expansionism and instated environmental provisions. Muskie's actions severed a nearly 100-year Republican stronghold and led to the political insurgency of the Maine Democrats.

Muskie's legislative work during his career as a senator coincided with an expansion of modern liberalism in the United States. He promoted the 1960s environmental movement which led to the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the Clean Water Act of 1972. Muskie supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the creation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and opposed Richard Nixon's "Imperial presidency" by advancing New Federalism. Muskie ran with Vice President Hubert Humphrey against Nixon in the 1968 presidential election, losing the popular vote by 0.7 percentage point—one of the narrowest margins in U.S. history. He would go on to run in the 1972 presidential election, where he secured 1.84 million votes in the primaries, coming in fourth out of 15 contesters. The release of the forged "Canuck letter" derailed his campaign and sullied his public image with Americans of French-Canadian descent.

After the election, Muskie returned to the Senate, where he gave the 1976 State of the Union Response. Muskie served as first chairman of the new Senate Budget Committee from 1975 to 1980, where he established the United States budget process.[b] Upon his resignation from the Senate, he became the 58th U.S. Secretary of State under President Carter. Muskie's tenure as Secretary of State was one of the shortest in modern history. His department negotiated the release of 52 Americans, thus concluding the Iran hostage crisis. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Carter in 1981 and has been honored with a public holiday in Maine since 1987.

Early life and education

[edit]Edmund Sixtus Muskie was born on March 28, 1914, in Rumford, Maine.[9][10] He was born after his parents' first child, Irene (born 1912), and before his brother Eugene (born 1918) and three sisters, Lucy (born 1916), Elizabeth (born 1923), and Frances (born 1921).[1] His father, Stephen Marciszewski, was born and raised in Jasionówka, Russian Poland[11] and worked as an estate manager for minor Russian nobility.[12] He immigrated to America in 1903 and changed his name to Muskie from "Marciszewski" in 1914.[2][13] He worked as a master tailor and Muskie's mother, Josephine (née Czarnecka) worked as a housewife. She was born to a Polish-American family in Buffalo, New York. Muskie's parents married in 1911, and Josephine moved to Rumford soon after.[14]

Muskie's first language was Polish; he spoke it as his only language until age 4. He began learning English soon after and eventually lost fluency in his mother language.[15] In his youth he was an avid fisherman, hunter, and swimmer.[16] He felt as though his given name was "odd" so he went by Ed throughout his life.[17] Muskie was shy and anxious in his early life but maintained a sizable number of friends.[18] Muskie attended Stephens High School, where he played baseball, participated in the performing arts, and was elected student body president in his senior year. He would go on to graduate in 1932 at the top of his class as valedictorian.[19] A 1931 edition of the school's newspaper noted him with the following: "when you see a head and shoulders towering over you in the halls of Stephen's, you should know that your eyes are feasting on the future President of the United States."[20]

Influenced by the political excitement of Franklin D. Roosevelt's election to the White House, he attended Bates College in Lewiston, Maine.[19][21] While at college, Muskie was a successful member of the debating team, participated in several sports, and was elected to student government.[19] Although he received a small scholarship and New Deal subsidies, he had to work during the summers as a dishwasher and bellhop at a hotel in Kennebunk to finance his time at Bates.[22] He would record in his diaries occasional feelings of insecurity among his wealthier Bates peers; Muskie was fearful of being kicked out of the college as a consequence of his socioeconomic status.[23] His situation would gradually improve and he went on to graduate in 1936 as class president and a member of Phi Beta Kappa.[14] Initially intending to major in mathematics he switched to a double major in history and government.[24]

Upon his graduation, he was given a partial merit-based scholarship to Cornell Law School. After his second semester there, his scholarship ran out. As he was preparing to drop out, he heard of an "eccentric millionaire" named William Bingham II who had a habit of randomly and sporadically paying the university costs, mortgages, car loans, and other expenses of those who wrote to him. After Muskie wrote to him about his immigrant origins he secured $900 from the man allowing him to finance his final years at Cornell. While in law school he was elected to Phi Alpha Delta and went on to graduate cum laude, in 1939.[25] Upon graduating from Cornell, Muskie was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar in 1939.[26]

He then worked as a high school substitute teacher while he was studying for the Maine Bar examination; he passed in 1940. Muskie moved to Waterville and purchased a small law practice—renamed "Muskie & Glover"—for $2,000 in March 1940.[27] He helped write Waterville's first zoning ordinance and was elected secretary of the Zoning Board of Appeals.[28]

Marriage and children

[edit]

Jane Frances Gray was born February 12, 1927, in Waterville to Myrtie and Millage Guy Gray. Growing up, she was voted "prettiest in school" in high school and at age 15, started her first job, in a dress shop.[29][30] At age 18, Gray was hired to be a bookkeeper and saleswoman in an exclusive haute couture boutique in Waterville. While there, a mutual friend tried to introduce her to Muskie while he was working in the city as a lawyer. She had Gray model the dresses in the shop window while he was walking to work. Muskie came into the shop one day and invited her to a gala event. At the time, she was 19 and he was 32; their difference in age stirred controversy in the town.[31] However, after eighteen months of courting Gray and her family, she agreed to marry him in a private ceremony in 1948. Gray and Muskie had five children: Stephen (born 1949), Ellen (born 1950), Melinda (born 1956), Martha (born 1958, d. 2006), and Edmund Jr. (born 1961).[10] The Muskies lived in a yellow cottage at Kennebunk Beach while they lived in Maine.[18]

U.S. Navy Reserve, 1942–1945

[edit]In June 1940, President Roosevelt created the V-12 Navy College Training Program to prepare men under the age of 28 for the eventual outbreak of World War II. Muskie formally registered for the draft in October 1940 and was formally called to deck officer training on March 26, 1942.[32] At 28, he was assigned to work as a diesel engineer in the Naval Reserve Midshipmen's School.[32] On September 11, 1942, Muskie was called to Annapolis, Maryland to attend the United States Naval Academy. He left his law practice running so "his name would continue to circulate in Waterville" while he was gone. He trained as an apprentice seaman for six weeks before being assigned the rank of midshipman.[33]

In January 1943, Muskie attended diesel engineering school for sixteen weeks before being assigned to First Naval District, Boston in May. Muskie worked on the USS YP-422 for a month. In June, he was assigned to the USS De Grasse (ID-1217) at Fort Schuyler in New York, where he worked as an indoctrinator.[34] In November 1943, Muskie was promoted to Deck Officer. He trained for two weeks in Miami, Florida at the Submarine Chaser Training Center. After that, Muskie was relocated to Columbus, Ohio to study reconnaissance in February 1944.[35] In March, he was promoted to Lieutenant (junior grade).[35] Muskie was stationed at California's Mare Island in April temporarily before formally engaging in active duty warfare.[35]

Muskie began his active duty tour aboard the destroyer escort USS Brackett (DE-41). His vessel was in charge of protecting U.S. convoys traveling from the Marshal and Gilbert Islands from Japanese submarines. The Brackett escorted ships to and from the islands for the majority of summer 1944. In January 1945, the ship engaged and eventually sank a Japanese cargo ship headed for Taroa Island.[36] After a few more months of escorting ships to and from the two islands, the ship was decommissioned. He was discharged from the Navy on December 18, 1945.[37]

Maine House of Representatives

[edit]

Muskie returned to Maine in January 1946 and began rebuilding his law practice. Convinced by others to run for political office as a way of expanding his law practice, he formally entered politics.[38] Muskie ran against Republican William A. Jones in an election for the Maine House of Representatives for the 110th District. Muskie secured 2,635 votes and won the election to most people's surprise on September 9, 1946.[39] During this time, the Maine Senate was stacked 30-to-3 and the House was stacked 127-to-24 Republicans against Democrats.[40]

Muskie was assigned to the committees on federal and military relations during his first year. He advocated for bipartisanship, which won him widespread support across political parties. On October 17, 1946, Muskie's law practice sustained a large fire, costing him an estimated $2,300 in damages. However, a yearly stipend of $800 and help from other business leaders who were affected by the fire quickly restarted his practice.[40]

Muskie's work with city ordinances in Waterville prompted locals to ask him to run in the 1947 election to become Mayor of Waterville, against banker Russel W. Squire. Perhaps due to incumbency advantage, Muskie lost the election with 2,853 votes, 434 votes behind Squire.[41] Some historians believe that his loss had to do with his inability to gain traction with Franco-American voters.[42]

Muskie continued his political involvement locally by securing a position on the Waterville Board of Zoning Adjustment in 1948 and stayed in this part-time position until he became governor. He later returned to the House to start his second term in 1948 as Minority Leader against heavy Republican opposition.[43] Muskie was appointed the chairman of the platform committee during the 1949 Maine Democratic Convention. During the convention, he brought together a variety of the political elite of Maine—notably Frank M. Coffin and Victor Hunt Harding—to plan a comeback for the party.[44] On February 8, 1951, Muskie resigned from the Maine House of Representatives to become acting director for the Maine Office of Price Stabilization. He moved to Portland soon after and was assigned the inflation-control and price-ceiling divisions.[45] His job required him to move across Maine to spread word about economic incentives which he used to increase his name recognition.[45] He served as the regional director at the Office of Price Stabilization from 1951 to 1952.[10] Upon leaving the Office he was asked to join the Democratic National Committee as a member; he served on the committee from 1952 to 1956.[10]

In April 1953, while working on renovations for his family home in Waterville, Muskie broke through a balcony railing, falling down two flights of stairs.[46] He landed on his back, knocked unconscious. He was rushed to the hospital, where he remained unconscious for two days.[46] Doctors believed that Muskie was in a coma, so they gave him comatose-specific medication which caused him to regain consciousness but start to hallucinate.[47] Muskie tried to jump out of the hospital window, but was restrained by staff members. After a couple of months, through physical rehabilitation and corrective braces, he was able to walk once more.[48]

Governor of Maine, 1955–1959

[edit]Gubernatorial campaign

[edit]

After establishing a prominent presence in the Maine State Legislature and with the Office of Price Stabilization, he officially launched his bid in the 1954 Maine gubernatorial race as a Democrat. Burton M. Cross, the Republican incumbent governor, was seeking reelection. Had he won, he would have been the fifth consecutive Governor to be reelected. Throughout the election Muskie was viewed as the underdog because of the Republican stronghold in Maine. Muskie acknowledged this himself by saying, "[this is] more as a duty than an opportunity because there was no chance of a Democrat winning."[18] A variety of personal reasons motivated his run. Muskie was deeply in debt owing five thousand dollars in hospital bills and maintained a rising mortgage. At the time of his election, the salary for the Governor of Maine was set at ten thousand dollars annually.[18] While he was campaigning he was offered a position involving full partnership at a prestigious Rumford law firm that maintained "clients and income that [Muskie] had not achieved in fourteen years of practice in Waterville."[18] His final choice reflected his 'society over self' mentality and decided to pursue the election.[49] He announced his candidacy for the office on April 8, 1954.[50]

Muskie ran on a party platform of environmentalism and public investment. His environmental platform argued for the establishment of the Maine Department of Conservation to "have jurisdiction of forestry, inland fish and game, sea and shore fisheries, mineral, water, and other natural resources" and the creation of anti-pollution legislation.[51] He stressed the need for "a two-party" approach to Maine politics with resonated with both Democratic and Republican voters wishing to see change. Muskie's central campaign slogan was "Maine Needs A Change" referencing the multi-year Republican stronghold.[50] He criticized the Republican Party for neglecting the environment, failing to restart the economy, underutilizing skilled labor forces, and ignoring public investment.[52]

He successively won the Democratic gubernatorial nomination, and then the general election by a majority popular vote on September 13, 1954. The upset victory made Muskie the first Democrat to be elected chief executive of Maine since Louis J. Brann in 1934. His election has been viewed as a causal link to the end of Republican political dominance in Maine and the rise of the Democratic Party.[18][53][54] After his win, he was asked by other Democrats running in elections outside of Maine to make a series of campaign stops.[55]

First term

[edit]

Muskie was inaugurated as the 64th Governor of Maine on January 6, 1955.[56] He was the state's first Roman Catholic governor.[57] Shortly after his assumption of the office, the next election cycle stacked the legislature with a 4-to-1 Republican-Democrat ratio against Muskie. Through bipartisanship and his aggressive personality[18] he managed to pass the majority of his party platform. Constituents pressured him to more aggressively pursue water control and anti-pollution legislation. In August, the Maine State Legislature authorized him to take extraordinary action to control the state's pollution standards. He used this authority to sign the New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Compact on August 31, 1955. This compact required member states to pay for anti-pollution measures collectively. Conservative members of the Chamber of Commerce fought back against Muskie in his attempt to allocate money to the compact and greatly reduced the amount paid.[58] One of the chief concerns of Muskie during this time was economic development. Maine's population was aging, putting pressure on welfare services. He expanded certain programs and cut down on others in order rebalance state spending.[6][59] Before leaving office Muskie signed an executive order extending the gubernatorial term to four years.[60]

He expanded the territory comprising Baxter State Park by 3,569 acres and purchased 40 acres (1.7 million ft2) of Cape Elizabeth from the federal government for $28,000.[61] He also created the Department of Development of Commerce and Industry and Maine Industrial Building Authority.[54] In February 1955, he was briefed on atomic energy power by the United States Atomic Energy Commission leading him to limit the expansion of atomic-powered electrical facilities.[62]

Second term

[edit]On September 10, 1956, Muskie was re-elected Governor of Maine with 180,254 votes (59% of the vote) against Republican Willis A. Trafton. He won 14 of the 16 counties. He began his second term by aggressively enforcing environmental standards. In 1957, he sanctioned a $29 million highway bond.[63] This bond funded the largest road construction ever undertaken by Maine. The highway included 91 bridges and was extended in 1960 and 1967 by Interstate 95.[59]

During his tenure as Governor he retained a reputation for increased spending in public education, subsidized hospitals, modernized state facilities, and cumulatively raised state sale taxes by 1%.[63] He added $4 million to infrastructure development focusing on roads and river maintenance.[64] Muskie pushed aggressive economic expansionism.[52][65] In 1957, he founded the Maine Guarantee Authority which combated economic maturation-related job loss making capital more accessible for business owners.[66] Muskie also sporadically lowered sales tax, increased the minimum wage and furthered labor protections leading to a marked increase in consumer spending.[67] He amended the constitution of Maine in order divert $20 million in public funds into private investment.[68] He increased subsidies to expensive institutions such as public primary and secondary schools as well as universities.[69] Although initially founded in 1836, the Maine State Museum was closed and reopened six times before Muskie permanently endowed it in 1958.[70]

His governorship exploited multi-factionalism in the Republican Party leading to a vast expansion of the Democratic Party in Maine. From 1954 to 1974, the party doubled in size, while the Republican Party steadily decreased from 262,367 to 227,828 registered members.[54] Numerous state politicians mimicked his political style to push their programs through various local governments and garnered electoral success.[54] His executive appointments of moderate politicians shifted the entire Republican establishment in the state to the left.[54] This shift garnered comparisons to Hubert Humphrey's influence in Minnesota and George McGovern's impact in South Dakota.[54] During his last months as governor he changed his office's term from two years to four years.[63] Shortly before leaving office he moved Maine's general election date from September to November conclusively ending the notion that "as Maine goes, so goes the nation".[71] This was attempted thirty-six times before Muskie brought about a constitutional amendment that moved the date.[72]

Muskie resigned on January 2, 1959, to take his seat in the United States Senate after the 1958 Senate election. He was succeeded by Republican Robert Haskell in an interim capacity until the Governor-elect, Democrat Clinton Clauson, was inaugurated. Muskie was officially succeeded by Clauson on January 6, 1959.[54]

United States Senate, 1959–1980

[edit]Elections and campaigns

[edit]

Muskie's first contestation for the Senate of the United States was in 1958. He announced his intent to challenge incumbent Republican Senator Frederick G. Payne on March 20, 1958.[73] Muskie won the election with 61% of the vote against Payne's 39%. Muskie's victory made him the first Democrat elected to the Senate in Maine, with the state's previous Democratic Senator having been appointed by the legislature.[74] He was one of the 12 Democrats who overtook Republican incumbents and established the party as the party-of-house during the election cycle.[75] The New York Times reported that during this election that the absentee ballots requested for Democrats increased considerable signaling voter-discontent with Republican ideology.[75] This election was considered the largest single-party gain in the Senate's history.[76]

He ran for a second term in 1964, running against Republican Clifford McIntire. Muskie won with 67% of the vote.

Election eve speech

[edit]His third campaign and election to the Senate occurred in 1970. During the 1970 elections, Muskie secured 62% of the vote against Republican Neil S. Bishop's 38%. The elections were seen as tumultuous due to the United States' involvement in the Vietnam War and rising unpopularity of incumbent president Richard Nixon. On the night of poll-opening Muskie gave a nationwide, 14 minute speech to addressed American voters following a similar address by Nixon. Dubbed the "election eve speech"[77][78][79][80] it spoke to American exceptionalism and against "torrents of falsehood and insinuation".[81] The speech was considered bipartisan and was well received by both parties. Political analysts believed that the speech influenced voting patterns during the election as there were thirty million listeners.[81] Commentators received the speech as "essentially evangelical"[25] and indicative of "a volcanic private temper but a soothing public manner".[81] The most famous passage from the speech was widely commented on by the public[82] for its biting nature and critique of "politics of fear":

I am speaking from Cape Elizabeth, Maine to discuss with you the election campaign which is coming to a close. In the heat of our campaigns, we have all become accustomed to a little anger and exaggeration. That is our system. It has worked for almost two hundred years—longer than any other political system in the world. But in these elections of 1970, something has gone wrong. There has been name-calling and deception of almost unprecedented volume. Honorable men have been slandered. Faithful servants of the country have had their motives questioned and their patriotism doubted. It has been led . . . inspired . . . and guided . . . from the highest offices in the land. ... We cannot make America small. ... Ordinarily that division is not between parties, but between men and ideas. But this year the leaders of the Republican party have intentionally made that line a party line. They have confronted you with exactly that choice. Thus—in voting for the Democratic party tomorrow—you cast your vote for trust—not just in leaders or policies—but for trusting your fellow citizens . . . in the ancient traditions of this home for freedom . . . and most of all, for trust in yourself.[78]

The Portland Press Herald on November 4, 1970, noted it akin to Franklin D. Roosevelt's fire-side chats "with video".[78] The speech has been the subject of numerous studies regarding "the dimensions of the televised public address as an emerging rhetorical genre of pervasive influence in contemporary affairs".[83]

In his fourth and final election, Muskie ran against Republican Robert A. G. Monks in 1976; he won 60% of the vote compared to Monk's 40%.[84] The elections coincided with the election of Jimmy Carter as president leading to a large influx of Democratic support,[85] though Carter lost Maine to incumbent President Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential election.

First and second term

[edit]

Edmund Muskie was sworn into office as U.S. Senator from Maine on January 3, 1959.[86] His first couple of months in the Senate earned a reputation for being combative and often sparred with Majority Leader, Lyndon B. Johnson, who subsequently relegated him to outer seats in the Senate. In the next five years, he gained significant power and influence and was considered among the most effective legislators in the Senate.[87] However, increased power and influence prompted supporters in Maine to label him "an honorary Kennedy", alluding to the indifference John F. Kennedy had to Massachusetts when first gaining political traction.[87] Muskie used the influence gain in his first two terms to push a vast expansion of environmentalism in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[88] His specific goals were to curb pollution and provide a cleaner environment. Occasional speeches on environmental preservation earned him the nickname "Mr. Clean".[89][90]

He served his entire career in the Senate as a member of the Committee on Public Works, a committee he used to execute the majority of his environmental legislation.[10] He served on the Committee on Banking and Currency from 1959 to 1970; the Committee on Government Operations until 1978.[10] As a member of the Public Works Committee, he traveled to the Soviet Union in 1959.[10] He sponsored the Intergovernmental Relations Act, later that year.[91]

In 1962, he co-founded the United States Capital Historical Society along with other members of congress.[92] The same year, members of Congress elected him to serve as the first chair of the Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution.[10] In 1963, he was the first to sponsor a new Act to regulate air pollution. The Clean Air Act of 1963 was written and developed by Muskie and his aide Leon Billings.[10]

His first major accomplishment was the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He assembled more than one hundred votes for the proposed legislation eventually passing it.[87] Also during 1964, he was critical of J. Edgar Hoover's management of the Federal Bureau of investigation. Muskie was upset by its "overzealous surveillance and its director's intemperance".[87] Muskie also sponsored the construction of the Roosevelt Campobello International Park near Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Brunswick estate.[10] Due to its international nature, Muskie was asked to chair a joint U.S.-Canada commission to maintain the park.[10] In 1965, he was again sponsored the Water Quality Act (later to be known as the Clean Water Act). He was the floor manager for the discussion and led to its passage in 1965 and its successful amendments in 1970.[10]

Alongside President Johnson's Great Society and War on Poverty programs, Muskie drafted the Model Cities Bill which eventually passed both houses of Congress in 1966.[53] Previously, combative with Johnson, Muskie began developing a more cooperative relationship with him. During Johnson's signing of the Intergovernmental Cooperation Act he said: I am pleased that Senator Muskie could be with us this afternoon. I believe that no man has done more to encourage cooperation among the National Government, the States, and the cities."[93] Also in 1966, Muskie was elected assistant Democratic whip and served as the floor manager for the Clean Water Restoration Act.[10]

During 1967 the popular sentiment in the U.S. was anti-war, which prompted Muskie to visit Vietnam to inform his political stance in 1968. Prior to his visiting the country, he debated with a congressman on a pro-war platform. After the trip, he became a leading voice for the anti-war movement and entered into the ongoing debate by speaking at the year's Democratic Convention. His speech was followed by "tens of thousands of protestors surrounded the convention and violent clashes with police carried on for five days."[94] He wrote to Johnson personally asserting his position on the Vietnam War. He made the case that the U.S. ought to withdraw from Vietnam as quickly as possible.[10] Months later, he wrote to the president again urging him to end the bombing of North Vietnam.[95] During the same year, he traveled with other Senators to the Republic of South Vietnam to validate their elections.[10]

Later, at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, he led the debate for the administration plank on Vietnam, which sparked public outrage. On October 15, 1969, he was welcomed to the green at Yale University to address the issues regarding his vote but chose to decline the offer and speak that night at his alma mater, Bates College, in Lewiston, Maine.[18] His decision to do so was widely criticized by the Democratic party and Yale University officials.[18] From 1967 to 1969, he served as the chair of Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee.[10] He voted against the appointment of Clement Haynsworth to the U.S. Supreme Court.[10]

Third and fourth term

[edit]His third term began in 1970 by co-sponsoring the McGovern-Hatfield resolution to limit military intervention in the Vietnam War.[10] During this time Harold Carswell was seeking appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. Muskie voted against him and Carswell failed the confirmation process.[10] Muskie also proposed a six-month ban on domestic and Soviet Union development of nuclear technologies to taper the nuclear arms race.[10]

As chair of the congressional environmental committee, he and fellow committee members including Howard Baker introduced the Clean Air Act of 1970,[96] which was co-written by the committee's staff director Leon Billings and minority staff director Tom Jorling.[97] As part of the act, he told the automobile industry it would need to reduce its tailpipe air pollution emissions by 90% by 1977.[98] He also co-wrote amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Act, more commonly known as the Clean Water Act, and urged his fellow Congress members to adopt it, saying "The country was once famous for its rivers ... But today, the rivers of this country serve as little more than sewers to the seas. ... The danger to health, the environmental damage, the economic loss can be anywhere."[99] The bill enjoyed bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress and was passed by the House on November 29, 1971, and the Senate on March 29, 1972. While congressional support was enough to enact it into law President Richard Nixon exercised his executive veto on the bill and stopped it from becoming law. However, after further campaigning by Muskie, the Senate and House of Representatives passed the bill 247–23 to override Nixon's veto.[100][101] The bill was historic in that it established the regulation of pollutants in the federal and state waters of the U.S., created extended authority for the Environmental Protection Agency, and created water health standards.[102][103] Also in 1971, Muskie was asked to join the Senate Foreign Relations Committee; he traveled to Europe and the Middle East in this capacity.[10]

After concluding his 1968 campaign for the White House he returned to the Senate. While in Chattanooga, the shooting of two black students at Jackson State College in 1970 by the Mississippi State Police, prompted Muskie to hire a jet airliner to take approximately one hundred people to see the bullet holes and attend a funeral of one of the victims. Critics in Maine described his actions as "rash and self serving" but Muskie publicly expressed no regret for his actions.[18] At an event in Los Angeles, he publicly stated his support for several black empowerment movements in California, which garnered the attention of numerous media outlets, and black city councilman Thomas Bradley.[18] In 1970, Muskie was chosen to articulate the Democratic party's message to congressional voters before the midterm elections. His national stature was raised as a major candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972. In 1973, he gave the Democratic response to Nixon's State of the Union address.[104] During this time, he was appointed the chair of the intergovernmental relations subcommittee.[105] Considered "a backwater assignment", Muskie used it to advocate for a widening of governmental responsibilities, limiting the power of Richard Nixon's "Imperial Presidency" and advancing New Federalism ideals.[106]

He served as the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee through the Ninety-third to the Ninety-sixth Congresses from 1973 to 1980. During this time, Congress founded the Congressional Budget Office in order to challenge Nixon's budget request. Prior to 1974, there was no formal process for establishing a federal budget so Congress founded the office under the auspices of the Senate Budget Committee. As chairman, Muskie presided over, formulated, and approved of the creation of the United States budget process.[3][4][5][6]

In 1977, he amended Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 along with others, to pass the Clean Water Act of 1977.[107] These new additions incorporated "non-degradation" or "clean growth" policies intended to limit negative externalities.[107] In 1978, he made minor adjustments to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and the "Superfund".[108]

Campaigns for the White House

[edit]1968 presidential election

[edit]Campaign

[edit]

In 1968, Muskie was nominated for vice president on the Democratic ticket with sitting Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Humphrey asked Muskie to be his running mate because Muskie, in addition to being of Polish Catholic heritage, had a more reserved personality that would contrast well with Humphrey's more ebullient style.[109]

The Humphrey-Muskie ticket narrowly lost the popular vote to Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew. Humphrey and Muskie received 42.7% of the popular vote and carried 13 states and 191 electoral votes; Nixon and Agnew won 43.4% of the popular vote and carried 32 states and 301 electoral votes, while the third party ticket of George Wallace and Curtis LeMay, running as candidates of the American Independent Party, took 14% of the popular vote and took five states in the Deep South and their 46 votes in the electoral college. Because Agnew seemed a weaker candidate than Muskie, Humphrey remarked that voters' uncertainties about whom to choose between the two major presidential candidates should be resolved by their attitudes toward the vice-presidential candidates.[110] While on the vice-presidential campaign trail in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Muskie was quoted as saying:

The truth is that Americans, born in this great tradition of humanism, still yield to prejudice and practice discrimination against other Americans. The truth is, having developed patterns and ways of living which reflect these shortcomings and weaknesses, we find it burdensome and difficult to – and all too often unacceptable to – do the uncomfortable things that we all must do to right the wrongs of our society.[18]

1972 presidential election

[edit]Background and primaries

[edit]

Before the 1972 election, Muskie was viewed as a front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination. Despite his strong polling, he continued to engage in tiring day-after-day speeches in various parts of the country.[18] When asked during an August 17, 1969 appearance on Meet the Press whether he would be a candidate in 1972, Muskie said it would depend on his being convinced that he could meet the challenges as well as his comfort.[111] On November 8, 1970, Muskie said he would declare himself a candidate only if he became convinced he was best suited to unify the country.[112] An August 1971 opinion poll showed Muskie outperforming Nixon.[113] In late 1971, Muskie gave an anti-war speech in Providence.[18] The nation was at war in Vietnam and President Richard Nixon's foreign policy promised to be a major issue in the campaign.[110]

The 1972 Iowa caucuses, however, significantly altered the race for the presidential nomination. Senator George McGovern from South Dakota, initially a dark horse candidate, made a strong showing in the caucuses which gave his campaign national attention. Although Muskie won the Iowa caucuses, McGovern's campaign left Iowa with momentum. Muskie himself had never before participated in a primary election campaign. Muskie went on to win the New Hampshire primary, but by a disappointingly small margin, and his campaign took a hit after the release of the "Canuck letter".[110]

"Canuck letter"

[edit]On February 24, 1972, a staffer from the White House forwarded a letter about Muskie to the Manchester Union-Leader. The forged letter, reportedly the successful sabotage work of Committee for the Re-Election of the President members Donald Segretti and Ken W. Clawson,[114][115] asserted that Muskie had made disparaging remarks about French Canadians which were likely to injure his support among the French-American population in northern New England.[116] The letter contained reference to French Canadians as "Canucks," a term used affectionately by some Canadians,[117] but regarded as offensive when referring to French Canadians,[118] prompting journalists to refer to it as the "Canuck letter."[119]

A day later, the same paper released an article that portrayed Muskie's wife, Jane as a drunkard and racially intolerant. On the morning of February 26, Muskie gave a speech to supporters outside of the Manchester Union-Leader offices in Manchester, New Hampshire. His speech was viewed as emotional and defensive; he called the newspaper's editor a "gutless coward."[116] Muskie gave the speech during a snowstorm, which made it appear that he was crying.[120] Though Muskie later claimed that the seeming tears were merely melted snowflakes, the press reported that Muskie broke down and cried, shattering the candidate's image as calm and reasoned.[121][122][123]

Evidence later came to light during the Watergate scandal investigation that, during the 1972 presidential campaign, the Nixon campaign committee maintained a "dirty tricks" unit focused on discrediting Nixon's strongest challengers. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigators revealed that the Canuck Letter was a forged document as part of the dirty-tricks campaign against Democrats orchestrated by the Nixon campaign.[90][124] Nixon was also reported to have ordered men to follow Muskie around and gather information. He tried to connect Muskie's acquaintance with singer Frank Sinatra to an abuse of office. Muskie often flew on Sinatra's private plane while traveling around California.[125][126]

1976 presidential election

[edit]In early July 1976, Muskie spoke with Jimmy Carter in a "productive" and "harmonious" discussion that was followed by Carter confirming that he considered Muskie qualified for the vice-presidential nomination.[127] Carter ultimately selected Walter Mondale as his running mate.[128]

U.S. Secretary of State, 1980–1981

[edit]

In late April 1980, he was tapped by President Jimmy Carter to serve as secretary of state, following the resignation of Cyrus Vance. Vance had opposed Operation Eagle Claw, a secret rescue mission intended to rescue American hostages held by Iran. After that mission failed with the loss of eight U.S. servicemen, Vance resigned. Muskie was picked by Carter for his accomplishments with senatorial foreign policy. He was appointed and soon after confirmed by the Senate on May 8, 1980, by a margin of 94–2.[94][131]

Draft Muskie movement

[edit]In June 1980, there was a "draft Muskie" movement among Democratic voters within the primaries of the 1980 presidential election. President Carter was running against Senator Ted Kennedy, and opinion polls ranked Muskie more favorably against Kennedy. One poll showed that Muskie would be a more popular alternative to Carter than Ted Kennedy, implying that the attraction was not so much to Kennedy as to the fact that he was not Carter. Moreover, Muskie was polled against Republican challenger Ronald Reagan at the time showing Carter seven points down.[132] Due to a political allegiance with Carter, he backed out of the contention.[133] Pressured by the Carter Administration, Muskie released the following public statement to Democratic voters: "I accepted the appointment as secretary of state to serve the country and to serve the president. I continue to serve the president, and I will support him all the way! I have a commitment to the president. I don't make such commitments lightly, and I intend to keep it."[133] An article by The New Yorker speculated that the move to back Muskie was a temporary flex of political power by the Democratic voter base to unease Carter.[134]

Afghanistan

[edit]In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan which prompted NATO to trigger its ally contract.[94] Muskie began his tenure as secretary of state five months into the invasion. He assigned Deputy Secretary Warren Christopher the tasks of managing the domestic side of the department while he participated in international deliberations.[135] Muskie met with Soviet diplomat Andrei Gromyko who categorically rejected a compromise that would secure the Soviet Union's withdrawal from Afghanistan.[136] Gromyko wanted the state department to formally recognize Kabul as a part of the Soviet Union.[137]

Soviet Union

[edit]Muskie was against the rapid accumulation of highly developed weaponry during the 1950s and 1960s as he thought that would inevitably lead to a nuclear arms race that would erode international trust and cooperation. He spoke frequently with the government executives of Cold War allies and that of the Soviet Union urging them to suspend their programs in pursuit of global security.[94] Muskie's inclinations were confirmed during the early 1970s when Russia split from the U.S. and accumulated more warheads and anti-ballistic missile systems. In November 1980, Muskie stated that Russia was interested in pursuing a "more stable, less confrontational' relationship with the United States."[138] He criticized the stances undertaken by Ronald Reagan multiple times during his presidential campaign expressing disdain for the calls to reject the SALT II treaty.[139] Muskie, throughout his political career, was deeply afraid of global nuclear war with the Soviet Union.[140]

Iran hostage crisis

[edit]On November 4, 1979, 52 American diplomats and citizens were held hostage by an Iranian student group in Tehran's U.S. Embassy. After the resignation of Cyrus Vance left a gap in the negotiations for the hostages, Muskie appealed to the United Nations (U.N.) and the government of Iran to release the hostages to little success. Already six months into the hostage crisis, he was pressed to reach a diplomatic solution.[141] Before he assumed the position, the Delta Force rescue attempt called Operation Eagle Claw resulted in the death of multiple soldiers, leaving military intervention a sensitive course of action for the American public. He established diplomatic ties with the Iranian government and attempted to have the hostages released yet was initially unsuccessful. On January 15, 1981, as Muskie was flying to address the Maine Senate in Augusta, President Carter called him as his jet was touching down at Andrews Air Force Base.[142] Carter alerted him that there was a possible breakthrough in the negotiations conducted by his deputy secretary Warren Christopher.[142] After the negotiations failed, Muskie instructed the state department to continue seeking an agreement for the hostages' release.[137] On January 20—the inauguration day of Ronald Reagan—the fifty-two hostages were handed over to U.S. authorities, a solution that had eluded Muskie and the entire Carter administration for 444 days and contributed to Carter's defeat.[141]

Muskie left office on January 18, 1981, two days before Carter's last day as president and the inauguration of Ronald Reagan.[135]

Later years

[edit]

Muskie retired to his home in Bethesda, Maryland, in 1981. He continued to work as a lawyer for some years. After leaving public office, he was a partner with Chadbourne & Parke, a law firm in Washington.[137] Muskie also served as the chairman of the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University as well as the chairman emeritus of the Center for National Policy.[143]

In 1981, he was awarded the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Dame, considered the most prestigious award for American Catholics.[144]

Tower Commission

[edit]In 1987, Muskie was appointed a member of the President's Special Review Board known as the "Tower Commission" to investigate President Ronald Reagan's administration's role in the Iran-Contra affair. Muskie and the commission issued a highly detailed report of more than 300 pages that was critical of the president's actions and blamed the White House chief of staff, Donald T. Regan, for unduly influencing the president's activities. The panel was notable as the findings of the report were directly critical of the president who appointed the commission.[145]

Muskie was critical of the commission decrying the "over-obsession with secrecy," noting that "there are occasions when it's necessary to hold closely information about especially covert operations, but even possibly other operations of the Government. But every time that you are over-concerned about secrecy, you tend to abandon process."[146] While underfunded, the commission did find that the Reagan administration ran a parallel policy directive at the same time they were publicly condemning negotiating for hostages.[147]

Death and funeral

[edit]

Muskie died at 4:06 AM EST on the morning of March 26, 1996, at the Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C., after seeking treatment for bouts of congestive heart failure.[148] He died two days shy of his 82nd birthday. Eight days prior he underwent a carotid endarterectomy in his right neck.[149] His assistant reported that he had suffered a myocardial infarction.[149] Some historians believe that his blood clots were brought on from frequent 8,421 mile (13,552 km) flights to Cambodia; he was asked to assist in stabilizing its government[150] on behalf of President Bill Clinton.[76]

Due to his service in the United States Naval Reserve during World War II, he was eligible to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia.[149][151] His ultimate rank of lieutenant had him placed in Section 25 of the cemetery.[152][153] Although he died on March 26, his grave stone initially noted that he died on the 25th. His wife, Jane, died on December 25, 2004, at age 77, due to health complications brought on by Alzheimer's disease.[30] She was buried next to Muskie and his grave stone was corrected to read "March 26, 1996".[154]

Muskie was memorialized in Washington D.C., Lewiston, Maine, and Bethesda, Maryland. At his Washington memorial, he was paid tribute to by a variety of U.S. senators and house representatives.[155] His alma mater—Bates College—held a memorial presided over by its president, Donald Harward.[155] On March 30, 1996, a publicly broadcast, Roman Catholic funeral was held in Bethesda at the Church of the Little Flower.[156] He was eulogized by U.S. president Jimmy Carter; U.S. Senator, George J. Mitchell; 20th United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Madeleine Albright; a political aide, Leon G. Billings; and one of Muskie's sons, Stephen.[155]

Legacy

[edit]Historical evaluations

[edit]

Historical evaluations of Edmund Muskie focus on the impact his actions and legislation had in the United States and the greater world.[76][157][158] His accomplishments in his home state have had him noted as one of the most influential politicians in the history of Maine.[6][76] Depending on the metric he is coupled with Hannibal Hamlin and James Blaine as the three most important politicians from Maine.[159][160][161] Muskie occupied all offices available in the Maine political system excluding state senator and United States representative. His political status in Maine is generally perceived favorably.[162] During his four-year term as Governor of Maine he initiated a constitutional amendment, invested heavily in infrastructure, and institutionalized economic development—effectively bringing Maine into the Golden Age of Capitalism.[163] Muskie ended the "as Maine goes, so goes the nation" political sentiment in the United States by moving Maine's general election date to November instead of September.[163] He preserved the cultural integrity of the state by endowing the Maine State Museum which was seen as critical to his public perception.[163] Although economic expansionism was historically seen negatively by the people of Maine, Muskie's policies were seen favorably as they were coupled with environmental provisions. His advocation for minimum wage increases, increased labor protections, and sales tax exemptions boosted consumer spending.[164][165] Muskie has been widely characterized as the catalyst for the political renaissance of the Democratic Party in Maine.[18][53][54] His election to the governorship signaled a fracturing of the Republican Party in the state and nearly tripled the number of Democrats in Maine between 1954 and 1974.[164][59]

Since Muskie left office as the U.S. Secretary of State, writers, historians, scholars, political analysts and the general public have debated his legacy. Particular emphasis is placed on his impact in the environmentalist and civil rights movement; bureaucratic advancement, and diplomacy. Overall supporters of Muskie point to an expansion of environmental protection, preservation, and security.[166] Numerous historians have noted him as "the father of the 1960s environmental movement in America".[76][88] His accomplishments in environmentalism established two of the foremost measures in U.S. environmental policy: the Clean Water Act Amendments of 1972 and 1977 and Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970 and 1977.[167] His contributions to the Clean Air Act were so great that the bill was nicknamed the "Muskie Act".[168][169][170] These two laws have been credited as the first major step to launching the wider environmentalism movement both in the U.S. and to some extent, the rest of the Free World.[171][172][173] Harvard University law professor Richard Lazarus summarized Muskie's legislative legacy with the following:

Senator Muskie's environmental law legacy is no less than stunning in terms of positive impact on the nation's natural environment. It takes little imagination to speculate what our national landscape would now look like if the economic growth we witnessed in the past four decades had not been accompanied by the environmental protections for air, land, and water provided by the laws that Senator Muskie championed in the 1970s.[174]

Muskie's influence on American diplomacy was detailed by the Office of the Historian with the following: "In the nine months Muskie served as Secretary of State, he conducted the first high-level meeting with the Soviet government after its December 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. During these negotiations, Secretary Muskie unsuccessfully attempted to secure the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan. [He] also assisted President Carter in the implementation of the "Carter Doctrine", which aimed to limit Soviet expansion into the Middle East and Persian Gulf. Finally, under Muskie's leadership, the State Department negotiated the release of the remaining American hostages held by Iran."[137][175] Many political commentators believed the bestowing of the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Carter to be an affirmation of this assertion.[141][176][177]

The public perception of his civil rights advancement has endured. A champion of the civil rights movement in the United States, he publicly criticized J. Edgar Hoover's Federal Bureau of Investigation, which was at the time considered political suicide as Hoover often spied and attempted to smear his opponents.[178][179] Muskie also was instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the creation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and developed the reform of lobbying.[76][180] His time as the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee from 1975 to 1980 include the formation of the United States budget process.[3][4][8] Because of this, he is known as the "father of the federal budget process".[5][6][181] David Broder of The Washington Post, noted that Muskie's leadership of the Senate's intergovernmental relations subcommittee was, in part, responsible for countering Richard Nixon's "Imperial Presidency" and advancing "New Federalism".[106]

Public and political image

[edit]

Muskie's early political career was helped by his physical appearance. Voters could relate to his public persona in ways that translated to relatively high voter turnout. R. W. Apple Jr. described Muskie as "long-jawed and craggy-faced" later noting that he "looked like the typical New Englander [with] a classic Down East accent."[157] Muskie's height has variously been recorded as 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) to 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m).[182][183] His height had him often compared to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and referred to by voters and media alike as "Lincolnesque".[87] He was often seen as "towering over" political candidates creating symbolic superiority and power.[16]

Known as a recluse, he disliked public attention and media speculation. Voters often associated with his "trademark directness, homespun integrity, and apolitical candor".[18] However, political aides have described him as having a "hot temper" and being demanding.[87] A notorious micro-manager, Muskie often required his aides to have "every speech and every position researched, analyzed and reported directly back to him."[87] While reserved and polite in public, when roused, it was reported that Muskie "had the vocabulary of a sailor".[16] His ability to command an argument was taken positively by voters as it signaled good leadership ability. Political opponents noted his "cutting intellect" as in-conducive to lengthy debates and voters noted it as a good quality to possess when negotiating with foreign leaders.[87] An official publication by Cornell University commented on his political image by saying: "he will be remembered for the quality of his mind; the toughness, the rigor, the common sense; and for another quality: the courage to take risks for what he saw as right".[184]

Known to be punctual, he was present 90% of Senate roll-call votes.[87] Although he was portrayed as socially rigid, he often broke from this mold and showed a personable side. While campaigning in cities, he often let students from the crowd run up to the stage and present a case for policy reform, unheard of at the time.[18]

Internship Program

[edit]The Edmund S. Muskie Internship Program is a professional exchange program supported by the United States Department of State.[185] It provides summer internship placements, career training, and financial support to Eurasian scholars and graduate students studying in the United States. The program was established by the United States Congress in 1992 fiscal year (Pub. L. 102–138, Sec. 227) and was named by the Freedom Support Act of 1992 (Pub. L. 102–511, Sec. 801). The Muskie program with a renewed format and scope was launched by Cultural Vistas in 2015. In the past, the program was administered by International Research & Exchanges Board and American Council of Teachers of Russian/American Council for Collaboration in Education and Language.

Honors and memorials

[edit]

He was awarded the Guardian of Berlin's Freedom Award from the U.S. Army Berlin Command in 1961.[186] In 1969, he was inducted in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences alongside Ted Kennedy, George McGovern, Walter Mondale, Shirley Chisholm, and Bella Abzug.[187]

At the conclusion of his political career, he held the highest political office by a Polish American in U.S. history, and also was the only Polish American ever nominated by a major party for vice president.[188] On the 100th birthday of Edmund Muskie, U.S. Senator Angus King spoke on the floor of the United States Senate in memoriam. King noted the following: "if you would see Ed Muskie's memorial, look around you. Take a deep breath. Experience our great rivers. Experience the environment that we now have in the country that we treasure."[6] Muskie received the keys to all three major cities in Maine: Portland, Lewiston, and Augusta.[186] He was given honorary citizenship to the State of Texas in 1968.[189] Numerous days have been named "Edmund S. Muskie Day": September 25, 1968 (Michigan), January 20, 1980 (New York), March 28, 1988 (Maine), March 1928, 1994 (Maine), and March 20, 1995 (Maine).[186] In 1987, the Maine State Legislature enacted Statute §A7 enacting "Edmund S. Muskie Day" on March 28. The statute was amended in 1989; Edmund S. Muskie Day is celebrated annually and is a public holiday in Maine.[190]

Muskie was given honorary degrees from Portland University (1955), Suffolk University (1955), University of Maine (1956), University of Buffalo (1960), Saint Francis College (1961), Nasson College (1962), Hanover College (1967), Syracuse University (1969), Boston University (1969), John Carroll University (1969), Notre Dame University (1969), Middlebury College (1969), Providence College (1969), University of Maryland (1969), George Washington University (1969), Northeastern University (1969), College of William and Mary (1970), Ricker College (1970), St. Joseph's College (1970), University of New Hampshire (1970), St. Anselm College (1970), Washington and Jefferson College (1971), Rivier College (1971), Thomas College (1973), Husson College (1974), Unity College (1975), Marquette University (1982), Rutgers University (1986), Bates College (1986), Washington College (1987), and University of Southern Maine (1992).[186]

Muskie was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the nation's highest honor—by President Jimmy Carter on January 16, 1981, for his work during the Iran hostage crisis, four days before stepping down from the presidency.[191] In 1984, the House of Representatives designated the Edmund S. Muskie Federal Building in Augusta.[192][193]

The American Bar Association honors lawyers who undertake pro bono work with the annual Edmund S. Muskie Pro Bono Service Award.[194] From 1993 to 2013, the United States Department of State ran the Edmund S. Muskie Graduate Fellowship Program in an effort to increase international study abroad.[195] In 1996, the Edmund S. Muskie Distinguished Public Service Award was founded by the Truman National Security Project to honor current or former elected officials.[196]

The Edmund S. Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine was named in his honor in 1990.[143] Muskie's papers and personal effects are kept at the Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine.[197]

See also

[edit]- List of people from Maine

- List of Bates College people

- List of Cornell University people

- List of governors of Maine

- List of United States senators from Maine

- List of secretaries of state of the United States

- List of United States presidential candidates

- List of United States Democratic Party presidential tickets

- Response to the State of the Union address

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ According to David (1970) and Witherell (2014) Muskie was born with the surname "Muskie"; his father changed his name to Muskie from "Marciszewski".[1][2]

- ^ According to Baldwin (2015), King (2014), and Nevin (1970), Congress founded the Congressional Budget Office under the auspices of the Senate Budget Committee of which Muskie first presided over. Muskie developed the notions of direct spending, discretionary allowances, annual appropriations bills, and continuing resolutions.[3][4][5] Muskie ultimately approved of and shaped the formation of the modern United States budget process.[6][7][8]

- ^ Muskie did not receive an official portrait in his capacity as Secretary of State. This photo was a photo op at the Southwest Federal Center in Washington.[129][130]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Witherell (2014), p. 4

- ^ a b David (1970), p. 10

- ^ a b c Joyce, Philip G. (2011). The Congressional Budget Office: Honest Numbers, Power, and Policymaking. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1589017580.

- ^ a b c "Backstage at the Budget Committee". The Washington Post. April 11, 1980. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: University of Southern Maine (December 11, 2014), Muskie Centennial Celebration (Part 1: Mark Shields), retrieved February 20, 2018

- ^ a b c d e f Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Angus S. King Jr. (March 27, 2014). Sen. King Honors Sen. Ed Muskie's Centennial Birthday. Event occurs at [time needed]. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ Ayres, B. Drummond Jr. (February 14, 1979). "Budget Balancers Warned by Muskie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ a b "Chronology of Muskie's life and work | Archives | Bates College". www.bates.edu. September 9, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Chronology of Muskie's life and work | Archives | Bates College". www.bates.edu. September 9, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ ampoleagle.com/ann-mikoll-a-trailblazer-p10493-226.htm "Stephen Marciszewski, came to Buffalo in the early 1900s after leaving his birthplace in Jasionewka, Poland. That part of Poland was occupied by Russia, and Stephen's father sent him away so that he wouldn't be conscripted into the Russian Army."

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 7

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 3

- ^ a b "Edmund Sixtus Muskie; People – Department History – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. viiii

- ^ a b c "Obituary: Edmund Muskie". The Independent. March 27, 1996. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Nevin, David (1970). Muskie of Maine. Ladd Library, Bates College: Random House, New York. p. 99.

... a man many deemed to be the single-most influential figure in Maine

- ^ a b c "Edmund S. Muskie | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. March 22, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 29

- ^ "Muskie, Edmund S." Maine: An Encyclopedia. April 24, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 36

- ^ Witherell (2014), pp. 39, 42–45

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 45

- ^ a b Nevin, David (1970). Muskie of Maine. Ladd Library, Bates College: Random House, New York. p. 32.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 62

- ^ Witherell (2014), pp. 63–64

- ^ Waterville (Me.) (1948). Annual Report of the City of Waterville for the Year Ending December 31, 1948. Maine Town Documents. pp. 18–21. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Witherell (2014), pp. 80–81

- ^ a b "Jane Muskie Dies; Husband's Emotional Defense Turned Race (washingtonpost.com)". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 82

- ^ a b Witherell (2014), p. 64

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 66

- ^ Witherell (2014), pp. 68–69

- ^ a b c Witherell (2014), p. 70

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 72

- ^ "Biography | Archives | Bates College". www.bates.edu. December 21, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 77

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 78

- ^ a b Witherell (2014), p. 79

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 86

- ^ Witherell (2014), pp. 86–87

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 89

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 93

- ^ a b Witherell (2014), p. 99

- ^ a b Witherell (2014), p. 109

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 110

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 111

- ^ Robert Mason, Richard Nixon and the Quest for a New Majority (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 2004), p. 153.

- ^ a b Blomquist 1999, p. 93

- ^ Blomquist 1999, pp. 92–93

- ^ a b Blomquist 1999, pp. 93–94

- ^ a b c Blomquist, Robert (1999). "What is Past is Prologue: Senator Edmund S. Muskie's Environmental Policymaking Roots as Governor of Maine, 1955–58". Valparaiso University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Palmer, Kenneth T.; Taylor, G. Thomas (1992). Maine Politics & Government. U of Nebraska Press. p. 30. ISBN 0803287186.

- ^ Blomquist 1999, p. 94

- ^ Blomquist 1999, p. 95

- ^ Witherell, James L. (2014). Ed Muskie: Made in Maine, The Early Years 1914–1960. Thomaston, Maine: Tilbury House Publishers. ISBN 978-0884483922.

- ^ Blomquist 1999, pp. 101–02

- ^ a b c "1946–1970 A Different Place". Maine History Online. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ root. "Edmund Sixtus Muskie". www.nga.org. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ Blomquist 1999, p. 104

- ^ Blomquist 1999, p. 106

- ^ a b c root. "Edmund Sixtus Muskie". www.nga.org. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 140

- ^ "Maine | history – geography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ "Economic development plans in Maine, 1957–present". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ DeFord, Deborah H. (2003). Maine: The Pine Tree State. Gareth Stevens. ISBN 978-0836851519.

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 141

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 142

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 150

- ^ Witherell (2014), p. 152

- ^ Witherell (2014), pp. 101–02

- ^ "Muskie To Run for Senate Seat". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. UP. March 20, 1958. p. 22. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ "DEMOS. TAKE KEY POSTS IN MAINE VOTE". Valley Times. AP. September 9, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "U.S. Senate: Mid-term Revolution". www.senate.gov. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Commentary: Happy 100th, Edmund Muskie". Press Herald. March 16, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ "Edmund S. Muskie: Late A Senator of Maine" (PDF).

- ^ a b c College, Bates. "Muskie Congressional Record: Election Eve Speech". abacus.bates.edu. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. August 18, 1975.

- ^ Rooks, Douglas (2016). Statesman: George Mitchell and the Art of the Possible. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1608933983.

- ^ a b c "The Muskie Moment | RealClearPolitics". Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Naughton, James M. (1972). "Muskie Home for Crucial Speech". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Velasco, Antonio de; Campbell, John Angus; Henry, David (2016). Rethinking Rhetorical Theory, Criticism, and Pedagogy: The Living Art of Michael C. Leff. MSU Press. ISBN 978-1628952735.

- ^ "1970 Elections: Democrats Gain in House and Governorships".

- ^ Schlesinger, Arthur Meier; Israel, Fred L.; Frent, David J. (2002). The Election of 1976 and the Administration of Jimmy Carter. Mason Crest Publishers. ISBN 978-1590843635.

- ^ "Muckie, Edmund Sixtus – Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nevin, David (1970). Muskie of Maine. Ladd Library, Bates College: Random House, New York.

- ^ a b "The Edmund S. Muskie Foundation – The Founder". www.muskiefoundation.org. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ "Supreme Court affirms Muskie's environmental legacy". May 17, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ a b "On Ed Muskie's 100th birthday, six things everyone should know". March 27, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ "Edmund S. Muskie | Muskie School of Public Service | University of Southern Maine". usm.maine.edu. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ "Mission & History". The U.S. Capitol Historical Society. July 11, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Remarks Upon Signing the Intergovernmental Cooperation Act". American Presidency Project. October 16, 1968.

- ^ a b c d "The Mainer at the Center of the Cold War | Maine Meets World". Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "Muskie Warns Protestors". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Early Implementation of the Clean Air Act of 1970 in California." EPA Alumni Association. Video, Transcript (see p. 2). July 12, 2016.

- ^ FRASER, JAYME (April 17, 2016). "Progressive Montana era inspired architect of Clean Air, Clean Water Acts". The Missoulian.

- ^ "Early Implementation of the Clean Air Act of 1970 in California." EPA Alumni Association. Video, Transcript (see p. 5). July 12, 2016.

- ^ Jim Hanlon, Mike Cook, Mike Quigley, Bob Wayland. "Water Quality: A Half Century of Progress." EPA Alumni Association. March 2016.

- ^ "Clean Water Act: Vetoes by Eisenhower, Nixon presaged today's partisan divide". www.eenews.net. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ Rinde, Meir (2017). "Richard Nixon and the Rise of American Environmentalism". Distillations. 3 (1): 16–29. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "History of the Clean Water Act". United States Environmental Protection Agency. February 22, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ "Edmund S. Muskie | Muskie School of Public Service | University of Southern Maine". usm.maine.edu. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York: Basic Books. p. 47. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ^ "The Edmund S. Muskie Foundation – The Founder". www.muskiefoundation.org. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Broder, David S. (March 31, 1996). "Muskie: Reason to Weep". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Blomquist (1999), p. 261

- ^ Blomquist (1999), p. 263

- ^ Gould, Lewis L. (2010). 1968: The Election That Changed America. Government Institutes. ISBN 978-1566639101.

- ^ a b c Nixon, Richard. RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon.

- ^ Elsasser, Glen (August 18, 1969). "Muskie Grim on Party Unity". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Presidential Bid Later-Muskie". Chicago Tribune. November 9, 1970.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York: Basic Books. p. 298. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ^ Bernstein, Carl; Woodward, Bob (2005). All the President's Men. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-89441-2.

- ^ Bernstein, Carl; Woodward, Bob (October 10, 1972). "FBI Finds Nixon Aides Sabotaged Democrats". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: NHIOP (July 22, 2013). "Edmund Muskie: Regarding the Canuck Letter (1972)". YouTube. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ Cheng, Pang Guek; Barlas, Robert (2009). CultureShock! Canada: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 262–. ISBN 978-981-4435-31-4.

- ^ "Canuck Definition & Meaning". Dictionary.com. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "16 worst political dirty tricks – 3 of 16". Politico. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ "Reality Itself Is Too Twisted". XPress Magazine. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ "Remembering Ed Muskie Archived April 27, 1999, at the Wayback Machine", Online NewsHour, PBS, March 26, 1996.

- ^ "FBI Finds Nixon Aides Sabotaged Democrats". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Woodward, Bob; Bernstein, Carl (2012). All the President's Men. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1471104664.

- ^ Theodore White, The Making of the President, 1972.

- ^ Fulsom, Don (2017). The Mafia's President: Nixon and the Mob. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1250119407.

- ^ Fulsom, Don (2012). Nixon's Darkest Secrets: The Inside Story of America's Most Troubled President. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1429941365.

- ^ Mohr, Charles (July 6, 1976). "Carter Describes Muskie As Qualified for Ticket". The New York Times.

- ^ "5 Vice Presidential Picks Who Were Key To Victory". NPR.org. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Secretary of State Edmund Sixtus Muskie". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Edmund Sixtus Muskie, U.S. Secretary of State". Flickr. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ College, Bates. "Muskie Congressional Record: Confirmation". abacus.bates.edu. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "Clinton Campaign Reminiscent of 1980 Race", The CBS News.

- ^ a b Goshko, John M.; Reid, T. R. (July 30, 1980). "Muskie Backs Carter, but Does Not Rule Out a Draft". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "The New Yorker Digital Edition : Aug 25, 1980". archives.newyorker.com. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ a b "Edmund Sixtus Muskie – People – Department History – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Edmund Sixtus Muskie – People – Department History – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Mihalkanin, Edward S. (2004). American Statesmen: Secretaries of State from John Jay to Colin Powell. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313308284.

- ^ "Secretary of State Edmund Muskie says the Soviet Union..." UPI. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "Secretary of State Edmund Muskie says the Soviet Union..." UPI. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell 2009: 641

- ^ a b c Mitchell 2009: 640

- ^ a b "Ed Muskie's Hostage Struggle Is Over, but the Families' Courage Is Still Being Tested – Vol. 15 No. 4". People.com. February 2, 1981. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ a b "Edmund S. Muskie | Muskie School of Public Service | University of Southern Maine". usm.maine.edu. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ "Recipients". The Laetare Medal. University of Notre Dame. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Steven V. (February 27, 1987). "The White House Crisis: The Tower Report Inquiry Finds Reagan and Chief Advisors Responsible for 'Chaos' in Iran Arms Deals; Reagan Also Blamed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell 1997: 639

- ^ "Tower Commission Report Excerpts". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Witherell (2014) p. 250

- ^ a b c Apple, R. W. Jr. (March 27, 1996). "Edmund S. Muskie, 81, Dies; Maine Senator and a Power on the National Scene". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "Unstable Cambodia". The New York Times. May 16, 1971. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ "Maine's Worcester Wreaths set out for Arlington National Cemetery". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Burial Detail: Muskie, Edmund Sixtus – ANC Explorer

- ^ "Segregated in Life, Integrated in Death | American Battle Monuments Commission". www.abmc.gov. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Knudsen, Robert C. (2008). A Living Treasure: Seasonal Photographs of Arlington National Cemetery. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1597972727.

- ^ a b c Memorial Tributes Delivered in Congress: Edmund S. Muskie, 1914–1996, Late a Senator from Maine. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1996.

- ^ "Senator Muskie Funeral, Mar 30 1996 | Video | C-SPAN.org". C-SPAN.org. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Apple, R. W. Jr. (March 27, 1996). "Edmund S. Muskie, 81, Dies; Maine Senator and a Power on the National Scene". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Baldwin, Nicoll, Goldstien, et al. 2015: 214

- ^ Witherell (2014), pp. 250–52

- ^ "Muskie, Edmund S.". Maine: An Encyclopedia. April 24, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Rolde, Neil (2006). Continental Liar from the State of Maine: James G. Blaine. Tilbury House, Publishers. ISBN 978-0884482864.

- ^ Witherell, James L. (2014). Ed Muskie: Made in Maine. Tilbury House Publishers and Cadent Publishing. ISBN 978-0884483922.

- ^ a b c Witherell (2014) pp. 130–42

- ^ a b Judd, Richard William; Churchill, Edwin A.; Eastman, Joel W. (1995). Maine: The Pine Tree State from Prehistory to the Present. University of Maine Press. ISBN 978-0891010821.

- ^ Coan, Ronald W. (2017). A History of American State and Local Economic Development: As Two Ships Pass in the Night. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1785366369.

- ^ Witherell (2014) p. 251

- ^ "Jimmy Carter: Clean Air Act Amendments – Letter to Senator Edmund S. Muskie". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Edmund S. Muskie Foundation – Muskie-Chafee Award". www.muskiefoundation.org. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "The Edmund S. Muskie Foundation". www.muskiefoundation.org. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "Clean Water: Muskie and the Environment". Maine History Online. Retrieved May 16, 2017.